How to beat piano performance nerves

Andrew Rumsey is our resident AMEB examiner, professional concert pianist, and education specialist. Andrew has played on some of the most prestigious stages in the world (including the Weill Recital Hall at Carnegie Hall in New York) and has a wealth of performance experience to draw upon. These opportunities have given Andrew first-hand experience with performance anxiety, and have led him on his own personal journey to overcome (and thrive under) pressure. He has also learned from some of the best in the business, both in Australia and abroad, spending years researching and trialing ways to beat piano performance nerves.

In this article, Andrew shares his insights on musical performance anxiety, and gives practical tips on what you and your students can do to improve performance and exceed expectations at upcoming exams or concerts.

What is performance anxiety?

Strictly speaking, it is our mental and physiological response to a perceived threat when completing an activity under pressure. In music, this usually manifests leading up to and during a performance.

Why do anxious nerves arise during performance or exams?

Cognitively, practising at home and performing in an exam are very different. In a practice session, there is relatively little pressure – nobody minds if mistakes are made, if something is wrong you can stop and repeat, and at any point in the practice you can ‘force quit’ and come back to it later. In a practice session there is no skin in the game!

By contrast, in an exam or recital, there is often an outcome that depends on the quality of the performance – the examiner, adjudicator, or audience will inherently judge the performance on some sort of criteria. We feel more pressure and heightened levels of stress in situations where there is something to lose.

How does this performance anxiety effect you?

As we mentioned earlier, it is a response to a perceived threat – this ‘fight, flight, or freeze’ response has been hardwired in us from back to the days of the unfathomable lightning storm and the sabre-toothed tiger; it’s a very primal part of the human mind. The surge of adrenaline that our body receives has several benefits, but it also comes with potential disadvantages.

The two fundamental parts of a stress response: mental and physiological

Our cognitive processes change in a performance situation, and we often find ourselves thinking negative thoughts, over-analysing how well we know the piece, and focussing negatively on the physical symptoms of the heightened arousal. These physiological cues are indicated by sweaty or clammy hands, increased heart rate, butterflies in the stomach, and sometimes feelings of nausea.

An important thing to consider is that a physiological anxiety is not really what we think it is! On its own, the heightened physical fight-or-flight state we experience in performance is known as “arousal” or “activation,” and is neither positive nor negative. What makes this activation harmful – or helpful – is the way that we interpret them, both mentally and emotionally.

As Dr Noa Kageyama states in his research Bulletproof Musician, “when combining a heightened state of physical activation with negative emotion, you get anxiety, which feels unpleasant and distressing. But, combining the same heightened state of physical activation with positive emotion, you get excitement, which may include many of the same symptoms but feels much more positive. Several studies have shown that focussing on ‘excitement’ and positive thinking rather than ‘anxiety’ leads to better outcomes, and that it is entirely possible to embrace the energy and heightened focus that comes with the increased adrenaline.” In other words, a ‘glass half full’ approach is statistically more likely to yield a better performance.

Stress Inoculation Therapy

How does one implement this positive thinking most effectively? One of the best things is to combine it with ‘stress inoculation therapy’ – performing under incremental or graded levels of pressure. Studies have shown that exposing oneself to manageable levels of stress results in the mind learning to tolerate, and eventually thrive under performance pressure. This also gives students an opportunity to practise this positive thinking in easier or lower risk performance situations.

Practice vs Performance mindset

As we said before, practising and performing are vastly different beasts, and music students are often skilled at practising practice, but less so at practising performance. The simplest way to implement stress inoculation therapy is to facilitate less stressful performance opportunities in the days or weeks, or even months, leading up to a performance or exam.

Here are some steps your students can take to gradually build up their stress tolerance, while incorporating positive thinking into their performance practices:

- Start by habitually visualising an audience or examiner being there in the practice room or at home with you.

- Practise recording the whole piece/program without stopping, under performance conditions (in school uniform/concert attire, on the exam instrument if possible).

- Perform the piece/program for familiar people – parents, siblings, close friends.

- Organise a performance in front of less familiar people, such as neighbours or acquaintances.

- Try performing in front of the most intimidating audience possible, such as a mock examiner, or a larger audience, or both!

Individual performance opportunities will be different for each student, but let the above method serve as a general guide. Each setting gets slightly more stressful, needing the student to practise positive thinking and cope with incrementally greater levels of pressure. There is no limit to how many steps you have can have, or how many times you can repeat each step as long as the stress/pressure level introduced gradually increases.

At the end of the day, music performance is about sharing our creativity, our passion, and the result of our hard-earned practice hours! In my mind, any method that helps us share this more confidently, effortlessly, and more enjoyably is worthy of exploration!

What to know more about Dr Noa Kageyama?

Kageyama is a violinist and performance coach at Juilliard, with a background in psychology. He has developed a comprehensive methodology for teaching students and musicians to become more confident, skilled – more bulletproof.

Visit the bulletproof website for lots of quality (and free) reading!

Prepared by Hugh Raine

More tips from our international friends

We consulted internationally acclaimed pianists and pedagogues on what works best for them and their students. Here is what they had to say about overcoming performance anxiety, and thriving under pressure.

Ivan Horvatic

Ivan Horvatic: Graduate of the Zagreb Academy of Music, graduate and faculty member at Zurich University of the Arts.

“Each student is different and therefore their preparation needs and routines will be quite specific to the individual. However, there are two mental exercises that my students and I often use to prepare for a concert that are extremely beneficial. The first: a few days before the performance, and at least once a day, the student should do a mental run-through of their piece/s to be performed, visualising the execution away from the piano. They should be aware of the movements being made and the sound being created. This is a fantastic way to find if there are any less confident sections. The second exercise is to be done right before the performance, sitting at the piano: breathe deeply into your feet, and imagine you are a big tree – your legs are roots going deep into the ground, your upper body is a trunk, and your arms and hands are branches and leaves through which the music flows far into the audience.”

Jason Stoll

Jason Stoll: Graduate of Juilliard School and Glenn Gould School of the Royal Conservatory of Music (Toronto), faculty at California State University, Northridge.

“Performing in front of an audience is such a thrilling part of what we do as musicians. Being able to connect wholly with an audience is truly something special and could make for a memorable experience for both performer and spectator. One important thing I do is make sure I have completely internalised my pieces a month before a performance – not just memorised but have the pieces ‘in my bones’ so that I am not worried about what the next note is. I tell my students to do this because being super prepared ahead of time helps with confidence and being able to play with fluency and conviction – then they just have to trust their preparation and can focus more on enjoying the actual performance.”

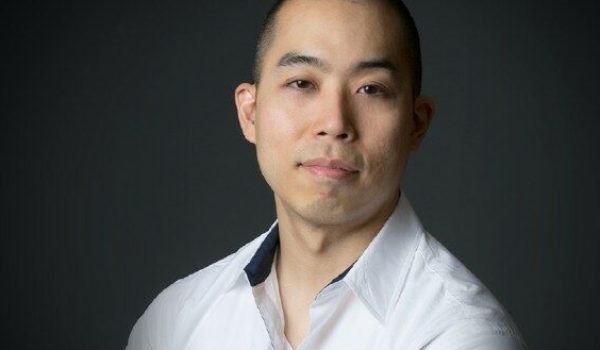

Dr Avan Yu

Dr Avan Yu: Graduate of Universität der Künste Berlin and Manhattan School of Music, winner of the 12th Sydney International Piano Competition.

“It is human nature to be afraid of the unknown. Therefore, for us to feel less nervous about something, we must become more familiar with it. If exams make you nervous, do some mock exams beforehand. If performances make you nervous, run through your pieces for your friends and family. You want to be as familiar with every aspect of the event in the period leading up to it – playing in your performance clothes, playing at that time of day, even become acquainted with the actual performance instrument. The end goal is to become so accustomed to all the extra-musical aspects beforehand that you are left with nothing else to do but to focus on the music and have fun!”

See Dr Avan Yu perform, 25th November 2023 07:00 Pm & 26th November 2023 2pm, as he leads the Willoughby Symphony Orchestra in an unmissable concert of verve and virtuosity. Information and tickets.